Today we have a guest post from Dr Keryn Pratt, UOCE Postgraduate Coordinator, and woman of many hats. Keryn has (obviously) completed her PhD, supervises students, and examines theses. Keryn introduces herself and offers some useful tips for the postgrad journey.

Dr. Keryn Pratt

As I write this post, I’m wearing a number of hats. The

first, from the point of view of my involvement in this blog, is my hat as

Doctoral & Distance coordinator for the College of Education. In this role I hold overall responsibility for

all postgraduate (non-initial teacher education) and distance matters within the

College, reporting to the Associate Dean (Research), Prof Jeff Smith. As the

name would suggest, I’m the first port of call for all doctoral matters, while

my colleague, Dr. Darrell Latham, as Masters Coordinator, takes the lead with Masters students. I’ve been in this role (or a variation) since 2010 and am

working to ensure we have a vibrant research student community within the

College, plus are supporting our many distance students.

As I write this post, I’m wearing a number of hats. The

first, from the point of view of my involvement in this blog, is my hat as

Doctoral & Distance coordinator for the College of Education. In this role I hold overall responsibility for

all postgraduate (non-initial teacher education) and distance matters within the

College, reporting to the Associate Dean (Research), Prof Jeff Smith. As the

name would suggest, I’m the first port of call for all doctoral matters, while

my colleague, Dr. Darrell Latham, as Masters Coordinator, takes the lead with Masters students. I’ve been in this role (or a variation) since 2010 and am

working to ensure we have a vibrant research student community within the

College, plus are supporting our many distance students.

The second hat I wear is as a thesis supervisor. I currently

supervise a number of doctoral students - but no masters students - they all

graduated! My research areas are in ICT and distance education, so most of my

students are in this area, although I do supervise across a wide range of

areas, as appropriate. As I was originally trained as a quantitative researcher

I’m often called on for input in Quant aspects of mixed methods research. This

is great, as it means I get to learn about a whole heap of different areas of

educational research.

My third hat is that of a lecturer. While there are -

obviously - no lectures involved at the thesis level, I teach in the course our

EdD students complete prior to beginning their thesis studies, plus all my

current teaching is at the postgrad level, so I’ve had many of our current

thesis students in one or other of my classes. Some of you have managed to

escape though . . . but I don’t take it personally :)

My fourth hat (I told you I had a number!) is that of a PhD

examiner. While I haven’t examined a huge number of theses (not including the

one I should be doing instead of writing this I’ve done 7 doctoral and seven

masters theses, and 24 masters dissertations), I have learned what this

examiner, at least, is looking for!

The final hat I wear is an ex PhD student. While my PhD was

completed a scarily long time ago (I graduated in 2000), and through a

different department (Psychology) I still remember some of the pain joy

of the process. I’ve shared some of my ‘pearls of wisdom’ with a number of our

current and past students - and while I don’t think completing one doctorate

gives anyone the ‘right’ answer, did learn some lessons which I’m happy to talk

about with anyone, in case they are of value to them too!

But this has got much longer than planned, so it’s time to

stop. I thought I’d end with a few points to keep in mind as you travel this

exciting, frustrating, confusing, wonderful, boring, exhilarating, unique road.

These are things I’ve found useful - but feel free to ignore them and find your

own tips/shortcuts etc.

1. Remember the point of your doctorate. It’s

not to change/save the world - it’s to pass! While how you do that is through

adding knowledge, it’s important to remember that this is just the first step

on a journey, and keep your examiners in mind - always. It’s not enough that

you think the information is important - they’ve got to think it too!

2. Remember the focus of your doctorate. It’s

very easy to get sidetracked - both in your reading and your writing. While you

do need to read widely at least initially, you have to stop reading (or at

least restrict it) at some stage. I ended up putting my research question

immediately above my desk, so that every time I glanced up from what I was

reading/writing I immediately saw it, and asked myself whether what I was doing

was addressing the research question. If it wasn’t, I put it aside for my

research life post-PhD.

3. Have somewhere to save bits you cut from your

thesis, and to record things you want to read/think about later. I found it

incredibly hard to just delete those sentences, paragraphs and sometimes (sob!)

pages that I’d worked so hard on. Somehow, copying them to another file, that I

could ‘come back to later’ made it so much better. Did I come back to them . .

. well no, but it did at least stop me leaving it all in for the poor examiner

to read!

4. Reference endlessly . . .I know you think

you’ll remember where you got that article, chapter etc, or that quote, the

idea you just noted - but you might not . . .and you don’t want to spend hours

going back through articles looking for where you found it. (Ok, so I did write

my thesis in the days before electronic articles, but it’s still an issue).

5. The little things do matter. Your formatting

needs to be easy to read and consistent, your referencing needs to be correct,

and if you say you are going to do a, b and c - then don’t do a, c and b. It

can be very off-putting for an examiner - and you want to keep them in a good

mood! I would recommend getting your formatting/heading styles sorted early,

and then use them for anything related to your thesis - it makes formatting at

the end so much less stressful. If you find you’re getting to the stage where

you can’t be bothered checking the line spacing under that heading, or whether

you’ve used that reference before (and so should say et al rather than listing

all the authors) - it’s time to do something else for a while.

6. Work out your timeline - and then ensure

you’ve allowed time for things to go wrong. If you want to finish in 3.5 years,

aim to finish in 3 - worst case you’ll finish early (apparently this does

happen . . .!), more likely you’ll be able to finish on time, once that chapter/ finding

participants /getting ethics takes longer than you planned. On that note, don’t

do a 2.5 year longitudinal study if you want to finish within 3 years! I know,

self-evident now . . .but somehow I missed that when I started!

7. When your supervisor (or anyone else)

criticises your thesis, it’s a good thing . . .honest! They are not criticising

you personally, they are just identifying ways that they think you could make

your work better. Getting criticism is not easy for anyone (that I’ve met

anyway!) and is something that academics struggle with (ask your supervisor how

they coped with their last rejection letter for a journal!). All supervisors

want the best for their students, and they want to work with you to make you

produce the best work when you can.

8. You cannot have too many copies of your

thesis - unless you have not labelled them clearly. You need to make sure you

have it saved in multiple places - and you also need to make sure you have

multiple versions. You don’t want to discover that the version you’ve carefully

saved in six different places is corrupt, and the only version you have left is

a month old . . . I used to save it with a new name (thesis date) each day, and

then add a, b, c etc as I made major changes during the day. At the end of each

day/week I’d go through and delete some copies so I didn’t have hundreds. It

did mean that when I went to print out the final version and found it was

corrupt, I didn’t have a complete

meltdown (note the emphasis on complete!).

9. There are lots of books/articles/blogs about

how to ‘do’ a thesis. While many of these are incredibly valuable, remember

that this is your journey, so you need to make it work for you. I found, for

example, that I write better later in the day, so started off with more mechanical

tasks, like checking referencing, or making changes, rather than launching into

writing. Others write best first, so need to do that. Experiment and see what

works best for you - there is no one right way to do it, but you might find

that what you thought would/wouldn’t work actually works really well.

10. And finally, enjoy it! This is supposed to be

fun! Well, it should be enjoyable anyway :-) This is something you’ve chosen to

do, and while it can and will drive you (and all those around you) completely up

the wall at times, keep reminding yourself of why you wanted to do it in the

first place - or plan the huge party you’ll have once it’s done! As part of

this, make sure you take advantage of the opportunities you get as research

students - the workshops, social events etc - especially if they are free! Just

remember not to spend all your time on these. Do balance your time though -

your doctorate should be like a job - so you are allowed (and definitely need)

to take time off. Make sure you take breaks, and the odd holiday - and don’t

spend all your time off thinking about it.

So what is the point of all this? Hopefully to introduce

myself to you, to make you feel like you’re not alone, and can come to me with questions, and maybe

give you some ideas about how you might go about this weird business of doing a

thesis and remain (relatively) sane. I look forward to hearing about everyone’s

journeys - and celebrating your graduations!

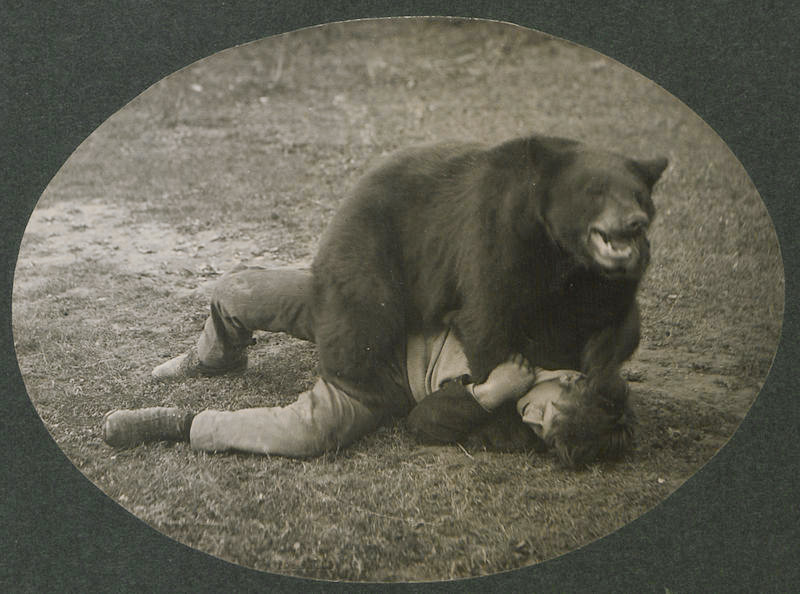

The Public Domain Review has tapped into many museum collections including the UK National Archives and subsequently their time line for material spans pre 16th Century right up to the 20th Century all of which have fallen out of copyright ergo available to use*. Excitingly they have multimedia content from images and films, to audio for you to explore! Including some cheeky GIFS like the first ever kiss caught on film! Saucy!

The Public Domain Review has tapped into many museum collections including the UK National Archives and subsequently their time line for material spans pre 16th Century right up to the 20th Century all of which have fallen out of copyright ergo available to use*. Excitingly they have multimedia content from images and films, to audio for you to explore! Including some cheeky GIFS like the first ever kiss caught on film! Saucy!